Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) are revisiting the way organic certification started a few decades ago. At the same time, many PGS have existed for over 40 years.

The development and professionalization of the organic sector, accompanied by increased international trade has called for third party certification to become the norm in most developed organic markets; nevertheless, PGS have never stopped to exist and serve organic producers and consumers eager to maintain local economies and direct, transparent relationships.

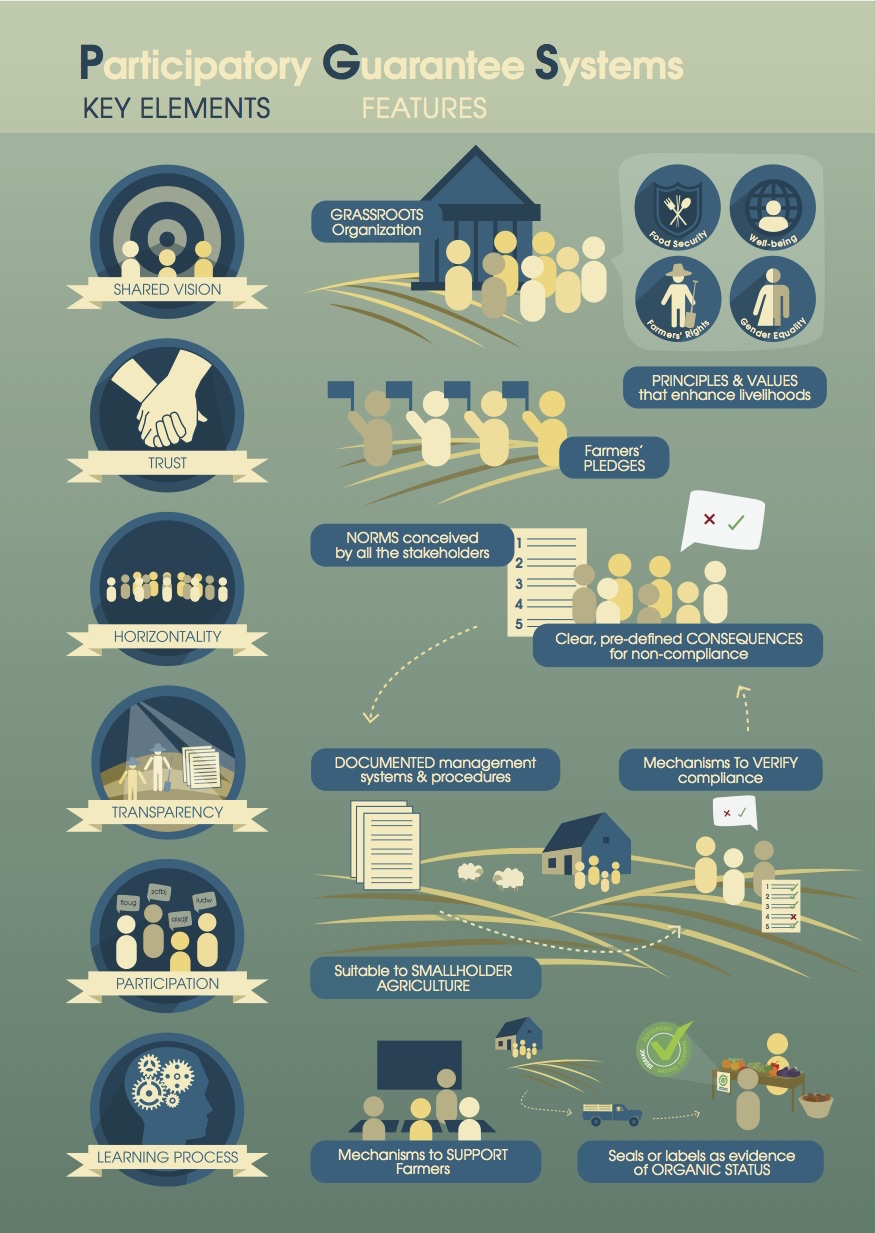

Thousands of organic producers and consumers are now verified through PGS initiatives around the world. Although details of methodology and process vary, the key elements and features remain consistent worldwide.

Thanks to the efforts of networks such as MAELA and IFOAM, the PGS concept has gained recognition and is now viewed by many as one of the most promising tools to develop local organic markets. But there are still many who are not familiar with PGS, who would like to know more about it or who are not so sure about how some issues are dealt with in these systems.

PGS Basics:

Third-party programs are doing an excellent job at what they were designed for and have vastly increased the global market and awareness of organic products. PGS offer a complementary, low-cost, locally-based system of quality assurance, with a heavy emphasis on social control and knowledge building. PGS, as a complementary method to third-party certification, is essential to the continued growth of the organic movement, especially if we want to include poorer smallholder farmers who have the most to benefit from organic.

It is ironic that in many countries we see the number of acres under third-party organic certification increasing quickly, while the number of certified organic farmers is hardly growing. Based on these numbers it would appear smallholder farmers are less interested in joining the organic movement than large agribusiness farms. Of course this is not true; it is only the process of third-party certification that smallholders are less interested in. Barriers to entry for third-party certification, including direct costs and paperwork, mean that many of the smallest and poorest farmers (those that have the most to gain by joining a system of committed organic production) cannot participate, and this hurts the growth of the organic movement as a whole.

The term Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) is relatively new – coined after the joint IFOAM-MAELA Alternative Certification Workshop in Torres, Brazil, in 2004. Over 40 participants representing PGS initiatives from 20 countries attended and many of these were well established by that time. Some PGS, like the Nature et Progrès in France, have been around since the 1970s. Others were established in the 1990s and most of the rest were established in the last 7-8 years.

IFOAM - Organics International is the only organization collecting, compiling, systematizing and disseminating comprehensive information about PGS worldwide. Every year, a global survey is carried out to monitor the development of PGS initiatives in terms of the number of farmers involved, the number of farmers certified, the number of developing PGS initiatives, etc. The results of this survey are translated into the Global PGS Map, which is updated on a regular basis, and are also published annually via “The World of Organic Agriculture – Statistics and Trends”. Updates on PGS are also published every month via the Global PGS Newsletter, a free electronic publication by IFOAM - Organics International.

The fast growth of the PGS movement over the last few years reflects the need to include smallholder farmers in the organic movement. In developing countries especially, most third-party certified farms rely on distant export markets to cover the cost of certification, so products from those farms are not available to local consumers. By bringing more farmers into a system of committed organic production, and linking that to direct and local sales, PGS offers much wider access to organic products to local consumers.

Because PGS initiatives directly link up consumers and farmers they may also help to provide organic food at a lower cost to poor consumers. In Brazil, for example, farmers and consumers in one PGS work together to come up with a fair price for bananas. By selling directly to the consumer, farmers realize a higher price for their products than when they were sold to distributors while consumers pay less than when they purchased conventional bananas from retail shops. A similar initiative is running in India. By meeting the needs of smallholder farmers and local and low-income consumers, PGS initiatives are poised to grow even more quickly as awareness of organic continues to grow globally. In turn, PGS has become integral to the future growth of the organic movement. Without them, organic will remain the bastion of the rich and educated leaving the poorest farmers and consumers unable to benefit.

It’s first essential to acknowledge that no system of certification or quality assurance is perfect. Farming is often a solitary profession; so unscrupulous people that want to cheat can generally find ways to do so. At the same time, PGS proponents believe that we must start with a foundation of trust and that organic farmers who make a public declaration to uphold the Principles of Organic Agriculture can, in fact, be trusted, and that intentional fraud accounts for only a minority of non-compliances.

The PGS approach to quality assurance begins by looking at the primary factors behind most non-compliant actions. These include a lack of understanding of organic rules and a lack of knowledge of organic techniques to solve specific production problems organically. PGS address these two factors in a variety of ways, but in general, they are based on guided peer review and support, as well as mutual knowledge building.

In addition, PGS initiatives make use of social control, which is effective only when local stakeholders have ownership and a direct hand in the certification mechanisms (as opposed to being answerable to a distant authority.) This requires locally based and non-hierarchical certification structures and mechanisms appropriate to the social context they are operating in. Finally, all PGS include guided on-site inspections.

Consumers are integral to the operation of a successful PGS. The exact role varies but includes helping with the initial development of the initiative, including standards and systems, to ongoing involvement in local, regional and national meetings, to participating in revisions and on-site farm appraisals. In some countries, consumers play an active role in distribution by running PGS cooperatives.

PGS In Practice:

IFOAM provides a number of resources to assist in starting a PGS program both online and in print, including links to PGS operation manuals and case studies from around the world. There are also the IFOAM PGS Guidelines, which elucidate key principles and characteristics of a PGS along with examples of how they have been practically incorporated in programs around the world. These guidelines will be soon updated to include more practical examples of real PGS initiatives that have been implemented in the past years.

Because there is no one set way to design a PGS initiative, consider contacting a PGS in a country where farmers face similar socio-economic conditions as farmers in your country.

Yes! Very much in the spirit of PGS, IFOAM has commissioned guidelines to start a PGS that uses examples to illustrate the various ways that different PGS around the world have integrated the principles and characteristics of a Participatory Guarantee System. You can pick and choose which systems would work best for your region and situation.

PGS initiatives around the world embrace certain principles and characteristics of a Participatory Guarantee System. The specifics of how they accomplish this vary, based on the social context they were created to serve. The “perfect” PGS in the United States wouldn’t fit well within the Indian social context at all for example. You can look to the IFOAM PGS Guidelines and other publications to see various examples. Also, look for an established PGS operating in a social context similar to your own.

A principle of PGS is that they are actively inclusive – seeking input from all stakeholders. Primary stakeholders obviously include farmers and consumers, but farmers' NGOs, consumer groups, environmental groups, and local and regional government agencies may all be involved in the PGS.

IFOAM has developed a Self-Evaluation Form (SEF) and an official IFOAM recognition program for PGS initiatives. The leading questions in the SEF take you through the principles and characteristics of PGS. You can apply for official IFOAM recognition of your PGS initiative and get access to the IFOAM PGS Logo, which you can use in your communication materials, but not on the organic products.

There is no international accreditation by IFOAM or any other agency for PGS initiatives. In fact, a "key characteristic" of the PGS movement is that they are locally focused and non-hierarchical, so the idea of accreditation doesn’t seem appropriate. However, IFOAM has developed a quality review system for PGS initiatives and offers an official IFOAM recognition to the applicant PGS initiatives that successfully pass an evaluation done by IFOAM and the IFOAM PGS Committee.

These questions are decided by the stakeholder farmers and consumers based on what is most appropriate to their situation. Different PGS have approached these questions differently – by country, region, state or even based on a specified number of miles. Some PGS have been legitimized across neighboring national boundaries.

A distinguishing characteristic of PGS is the lower direct costs as compared to individual third-party certification. Different PGS require different levels of farmer involvement but, at a minimum, farmers (and hopefully also consumers) are integrally involved in peer- reviews of each other’s operations. This is seen by many as one of the significant benefits of a PGS because it encourages the sharing of information between farmers and general capacity building. Farmers are also usually involved at the local level indirectly deciding on standards adopted, questions of certification as well as consequences for irregularities based on pre-agreed upon guidelines for managing non-compliance.

PGS place a high emphasis on the fact that they aren’t hierarchical and run in a more decentralized fashion. PGS is a system of quality assurance, not a system of production. Both PGS and third-party certification systems are based on the same Principles of Organic Agriculture, so allowable inputs in PGS certified organic agriculture are generally the same as those in third-party certified Organic Agriculture.

Some of the ways PGS initiatives have approached answering specific questions include but aren’t limited to:

- An advisory board, formed by representatives of the different stakeholders involved in the process, that makes decisions about specific products and practices;

- Use of an internationally recognized standard for Organic Agriculture, such as the IFOAM Standard;

- Use of other information sources, like the Organic Materials Research Institute (OMRI) that provides a list of allowable and prohibited products.

- Official or unofficial link-ups with a regional third-party certifier that can help advise on specific inputs and practices.

- Subscribing to an “official” production standard (for example the NOP in the US or the NPOP in India) which provides a considerable amount of support material to help answer such questions.

PGS and Organic Quality:

It’s not unreasonable to expect that a local farmer growing the same crops in the same region will be amongst the most knowledgeable people to handle an on-site assessment of a neighboring farm. In fact, one would expect them to know more about what’s going on at a neighbor’s farm than someone coming from thousands of miles away who has only read a briefing on the crops and region being visited.

That being said, all PGS initiatives have specific inspection documents to lead people untrained in conducting inspections through the necessary steps of a complete farm visit. Many PGS initiatives also conduct training for the reviewers (farmers, consumers and other members of the PGS) before they are sent to an on-site peer-review visit. These appraisals are also a way to verbally re-check that the farmer being visited actually understands the Principles of Organic Agriculture they are committing to, so peer-reviewers are led to do more than just a check on the physical farm as they are also directed by the document to ask leading questions to ascertain the farmer’s understanding. This leads to the sharing of ideas and organic practices and solutions that are specific to that area, so the result is of benefit to both the farmer and the reviewer.

Social Control only works when:

- Producers in a local group feel ownership and responsibility for the system;

- there are pre-agreed upon consequences for non-compliant actions;

- the pre-agreed upon consequences are perceived as appropriate (not too harsh, not too bland)

- there are consequences to the all for not taking action when they see the non-compliance of an individual farmer.

Including producers and various stakeholders from the beginning in deciding consequences for non-compliances satisfies these factors.

PGS philosophy is that a non-compliance means that the farmer needs more knowledge of Organic Principles and Organic Techniques (to solve the challenge organically). Basically, this review process is not targeted at a punishment; it allows for improvement. So often, consequences for less serious and especially inadvertent first-time mistakes are purposefully less harsh and actually a trigger for more support of that farmer. The resulting social attention (in addition to the education) also acts to minimize the chance that the farmer will make the same mistake again. In many PGS initiatives, unreported non-compliances discovered on one farm in a local group also have consequences to the entire local group of farmers.

Only a few PGS initiatives have integrated product testing into their operation. The decision to do so was important to the stakeholders of those programs. Again, the choice to include such processes depends on a decision by the stakeholders involved regarding the need for it, as well as their capacity to bear the corresponding costs.

Organic is a system of production and PGS is, in fact, a clearly documented system of quality assurance for organic farm products that results in a written certificate of the same. The steps taken to make this claim are consistent, codified and credible so PGS is clearly a certification system.

The PGS approach to certification is non-hierarchical and uses less paperwork than a third-party certification system. This sometimes can confuse people, but that doesn’t mean PGS is less of a system to guarantee the organic integrity of products or a certification system. PGS are developed in order to be appropriate to the farmers that they deal with. For example, the importance that PGS place on social control to avoiding (and reporting) non-compliances requires that the farmers are fully invested in the certification program – “their” certification program, and this necessitates a non-hierarchical approach.

In addition, PGS programs take the view that, especially with small farmers, most non-compliance issues are actually because of a lack of knowledge. As a result, knowledge sharing and capacity building for farmers are integral to PGS. The deep involvement that farmers (and often local consumers) have in the certification process is seen as entirely appropriate and necessary to provide a credible guarantee that products meet organic criteria.

Some other requirements for PGS include mechanisms to ensure that farmers understand the organic standards they are committing to, participate in peer -reviews (of their own farm and of one other farm) and making publicly recorded pledges or declarations to uphold the organic standard. Where appropriate, some PGS initiatives have included mandatory attendance to training sessions at key times of the growing season.

PGS and third-party certification systems are complementary and strengthen each other. PGS programs are focused on and better suited to small-farmers and direct markets, which brings many farmers that wouldn’t have considered third-party certification into a system of committed organic production. In this way, it provides a greater number of consumers with access to affordable, quality-assured Organic products that would not otherwise have been available.

This helps the Organic Movement as a whole to grow which will increase the demand for third-party certification. For example, some of the many newly certified PGS farmers will invariably want to access export or large processing markets that are better served by Third Party systems, which they could do sometimes individually but also through an ICS. PGS make an excellent base for ICS programs because many of the basic structures are already in place. Therefore PGS and third-party certification serve different markets and different operators, without any need for competition between the two systems.

Trying to discredit PGS as valid systems for organic quality assurance and certification and impose third-party certification as the only possible system for guaranteeing the organic quality of products, leads to unnecessary conflict which hurts the Organic Movement and limits access for low-income consumers to organic products in developing markets.

- Less paperwork in PGS;

- More commitment and responsibility of farmers in the certification process (including inspections and consequences) in PGS;

- Certification mechanisms in PGS are designed to be appropriate to the local social context and small-holder farmer they are serving;

- PGS are often more inclusive of new/transitioning Organic Farmers;

- Involvement of Consumer is encouraged and sometimes even required in PGS;

- Use of social control by involving and empowering local stakeholders thereby giving them “ownership” of the certification process is essential for PGS;

- Certification is given on “whole farm” basis rather than for single commodity products in PGS;

- Usually, individual farmers own their own PGS certificates, while in ICS the certificate is owned by the farmers' group, an NGO or the export company.

- More empowerment and freedom in the marketplace with PGS as compared to ICS where farmers are bound to sell only the (possibly limited) products that were certified and that through the group that holds the certificate.

PGS require more work and involvement from the farmer. Many third-party ICS programs are subsidized by the export companies, so the actual cost to farmers is small. If the export market is good, there may not be an advantage to the farmer at all. On the other hand, ICS Certification for export markets usually only offers certification of the product that is exportable. PGS programs offer whole-farm certification allowing farmers to market all their products as organic even to local markets. PGS also leave ownership of the certificate with the farmer which is not always the case with ICS systems. This gives the farmer the ability to seek out the highest paying buyer. Finally, there is a high emphasis based on capacity building in PGS. The learning experience of sharing with other farmers can lead to new cropping ideas and faster improvement of agricultural techniques that are appropriate to each context.

The two systems of certification complement each other. PGS, with low direct costs and the heavy emphasis placed on the involvement of the farmers and local consumers, is well suited to small farmers selling more locally. Furthermore, because PGS procedures are more flexible they tend to be more inclusive and appropriate for the local social context they serve. For example in India, PGS programs challenged by low literacy levels of their farmers decided to use video records for the farmers’ applications and declaration statement rather than a written statement. Third-party certification, on the other hand, with the heavy emphasis placed on detailed paperwork and external auditing may be frustrating and unnecessarily burdensome for such farmers selling locally and directly, but the mechanisms are absolutely necessary to provide credible organic quality assurance to customers far away from the farmers they are buying products from, as it happens in the global exports market.

It depends on the country. Organic is an internationally recognized system of production. At this time, however, some countries have legislation that limits the use of the term only to those operations that have gone through a specified system of certification. In some countries (including US, EU, Japan) the system of certification is limited to third party certification. In other countries, it includes both PGS or third-party systems of certification (Brazil, Bolivia, New Zealand). Many countries don’t have legislation one way or the other (Australia, India for domestic organic products).

Usually, PGS farmers receive a certificate they can use to show their PGS organic status. In addition, many initiatives allow the use of a PGS logo on stickers or stamps that are put directly on the products. In some countries, including India and the United States, PGS farmers are listed on the internet and in India information is available through an SMS-text messaging system, linked to labels on PGS products at the point of sale.

The main focus of PGS is to encourage local and direct relationships between farmers and consumers. Generally, exporting is done on larger scale farms and over great distances where both the farmer and consumer become anonymous. Third-party certification programs have mechanisms to deal effectively with those situations. That being said, neighboring countries have forged relationships with each other to facilitate trade in PGS products to a limited extent. The Brazilian legal framework recognizes PGS at the same level of third-party certification, meaning that a PGS farmer could also export the Organic products and it is estimated that 20% of PGS Certified Organic products are sold outside the country. Of course, this depends on the regulations of both exporting and importing countries.

Third-Party Certification mechanisms were created within the context of a need to provide auditable security for large processors and markets buying anonymous organic products on the open market. PGS initiatives, on the other hand, arose out of a different context – the need to provide affordable and inclusive quality assurance to small-holder farmers selling locally and more directly. As a result, the two systems complement each other quite well, so in general, farmers selling into anonymous distribution channels would be better served using a third-party certification approach rather than PGS.

That being said, there are situations where PGS products could be successfully sold to large supermarkets, but the chain of custody needs to be tightly controlled. For example, a supermarket chain in the US is interested in carrying PGS products, but the products are to be sourced only from local farmers and are highlighted as such on the store shelves.

Likewise, PGS doesn’t exclude value-added or processing in situations of closed sourcing. For example, a juice company producing a brand of orange juice sourced directly from a regional group of PGS farmers, processed, bottled, boxed and labeled as such could be an attractive and quality assured product that is finally sold on a distant supermarket shelf.

While there are cooperatively run shops that only sell PGS Organic products (as well as third-party certified Organic shops) such outlets are the minority, and most small retailers sell a diversity of products that could conceivably be misrepresented by an unscrupulous shopkeeper. In such a case, most countries already have consumer protection laws (or “Fair Trading Acts”) to deal with conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive consumers.

International organizations including IFOAM, MAELA, UN-FAO, have all been explicitly and proactively supportive of the need for PGS as alternative means for small-holder farmers to enter a system of committed organic production and to provide more consumers with quality assured organic products.

The International Task Force on Harmonization stated the need for consideration of PGS as a means of Organic quality assurance. Many international third party certification agencies are also looking at PGS programs as potential partners especially as a way to strengthen ICS programs or to reach out to a greater number of farmers that might be interested in access to international or processing markets.

PGS have received increased attention especially between 2011 and 2012. They were included in the international debate on food security and sustainable development. The concept was discussed and PGS initiatives were presented as examples and references in sessions taking place during major international conferences, from the IFOAM OWC in September 2011, to the high level 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio +20).